There are a lot of moving pieces this offseason for North Carolina basketball, which is set to lose a good chunk of frontcourt talent. However, Oklahoma transfer Brady Manek is here to help ease this transition phase.

Day’Ron Sharpe will head to the NBA Draft. Garrison Brooks and Walker Kessler will play for SEC programs next season. One of the primary objectives for Hubert Davis, moving forward, must be to restock North Carolina’s pool of interior talent. In the interim, though, UNC projects to have a strong duo at the 4 and 5 next season.

Armando Bacot, one of the most improved players in the ACC this season, is going through the NBA Draft process, but he’s a lock to return next season. It may be for just one season, but the Manek-Bacot pairing fits nicely on offense, along with the rest of North Carolina’s returning talent.

For the first time in years, Manek will provide UNC with a legit stretch option in the frontcourt. Here’s a look at what Manek brings to the table, how North Carolina can help integrate his skill set and how it could look partnering up with Bacot and Caleb Love.

Altered DNA in Chapel Hill

Throughout the Roy Williams era, North Carolina basketball took on a certain aesthetic on offense. Push the ball in transition, run the secondary break when primary is taken away, pound the paint and maul teams on the offensive glass.

This is painting with a bit of a broad brush. Even in recent years, Williams added new tactics to the repertoire; over his final two seasons as coach, UNC mixed in continuity ball screen actions and Horns sets. That’s not exactly splitting the atom in terms of scheme, but it’s still a willingness to adapt.

Of course, during this same two-year stretch, North Carolina also suffered from a nearly-complete power outage in terms of perimeter shooting.

Davis must now push things even further. The ways in which he decides to use Manek — a crucial offseason addition for UNC — will serve as an early indicator for how that process may go.

The bottom falls out

The 2019-20 season was the nadir for Williams. The disappointment from that campaign clearly still stung at the time of his retirement. Marred with injuries and ill-fitting pieces, North Carolina’s offense finished 77th nationally in adjusted efficiency, per KenPom. That’s really not such a bad number, but by UNC’s lofty standards: it’s a first-world crisis.

That season, only 28.9 percent of North Carolina’s field goal attempts were of the 3-point variety; UNC ranked No. 306 nationally in 3-point attempt rate. The Tar Heels shot just 30.4 percent on those looks, too, the lowest number since Williams took over the program.

With a promising 2020 recruiting class landing in Chapel Hill, the 2020-21 season seemed to hold plenty of promise for the Heels — minus, you know, having to play basketball during a global pandemic. That was less than great.

However, the team’s shooting woes wouldn’t disappear just because one season ended and another started. That’s not really how this works.

In fact, there were reasons for concern, especially with a crowded frontcourt, stocked with talented non-shooters. North Carolina would also part ways with its top three shooters from the 2019-20 season: Cole Anthony, Brandon Robinson and Christian Keeling. This spelled trouble.

Predictably, North Carolina’s perimeter shooting slumped. The team’s 3-point attempt rate dropped to 27.9 percent — No. 336 in Division I. In terms of 3-point percentage, that climbed slightly to 31.8 percent, the second lowest number under Williams.

If not for Kerwin Walton, who had one of the best 3-point shooting seasons for a freshman in ACC history, this would’ve been a disaster. (Walton, ultimately, was this team’s MVP.)

In the end, UNC saw its effective shooting (48.3 eFG%) and adjusted efficiency rise. This, however, was bolstered by the team’s power on the offensive glass: 40.9 percent (No. 1).

Straight Shooter: Brady Manek

It’s interesting to see the differing approaches for how programs tried to extract value from the transfer portal this offseason. For instance, some teams used it to address specific needs — an effort to satisfy a roster limitation. Programs with several key pieces set to return, like North Carolina, could use the portal to add one last necessary ingredient to the roster.

UNC valued someone with Manek’s offensive profile, and that’s exactly what the new staff went out and got. Now, for the first time since Luke Maye left, North Carolina will enter a season with a reliable, proven stretch big man.

This is an addition not only of another 3-point shooter, but also a shooter that can threaten defenses from a less common position.

Manek will be 23 at the start of next season; he’s been in college basketball for a long time, arriving at OU in the same 2017 recruiting class as Trae Young. (As the star point guard of the Atlanta Hawks, Young has already appeared in an NBA All-Star game and won at least one playoff series.)

During Manek’s time in Norman, he became well acquainted with the 3-point arc. While appearing in 122 games (111 starts), the 6-foot-9 Manek drained 235-of-628 3-point attempts (37.4 3P%).

Dating back to the 1992-93 season, only two Big 12 players recorded 600+ career 3-point attempts, shot at least 36 percent on 3-point looks and recorded 600+ rebounds. Manek and Buddy Hield, a former OU star now with the Sacramento Kings, are the only two to hit those benchmarks.

Going through Bart Torvik’s shot data, Manek is one of 19 high-major players 6-foot-9 or taller — since the 2007-08 season — to shoot above 37 percent from downtown on at least 10 3-point attempts per 100 possessions.

PnP Shooting

A quick glance at Manek’s numbers paints rather simple picture: he’s a good 3-point shooter. Those numbers didn’t occur in a vacuum; there’s context to everything. Manek is more than just a standstill shooter.

With a smooth, high release, Manek can splash jumpers over the top of closeouts. He can also shoot off movement. This opens up a world of possibilities for UNC, starting with the pick-and-pop.

According to Synergy Sports, Manek scored 0.99 points per possession on a combination of pick-and-pops and slip-screen jumpers during his career at OU. That’s solid.

Manek’s proficiency as a pick-and-pop shooter will be a real boon for North Carolina’s offense, regardless of opponent ball-screen coverages.

When opposing defenses Ice ball screens, Manek can simply float to the middle of the floor for a clean look.

Due to his height and high release point, the weak-side stunt (Cade Cunningham in the above clip) must come hard if it’s to really bother Manek. Will ACC foes be able to hard close on Manek, deny obvious passing outlets and force him to drive?

When opponents want to heat things up on the basketball, Manek can be a release valve at the point of attack. These screens from Manek can free up the primary ball handler and loosen the defense — putting opponents into rotation.

When Manek sets the ball screen, the offense generates a little advantage; this forces the defense to make a decision. Stunts, closeouts, synchronized rotations. As the advantage builds, defenses must be able to communicate and make multiple help efforts to stymie the action. This is a challenge.

On this possession, Jericho Sims of Texas comes to the level of the screen between Manek and Austin Reaves, which triggers a quick re-screen handoff action. Reaves does a better job stringing the ball-screen action out before kicking it back to Manek. Jase Febres (No. 13) tries to perform a weak-side stunt on Manek; instead, it turns into a clunky closeout. On the back side of the play, Greg Brown is slow to rotate over on Alondes Williams. Brown tries to react and closeout on Williams, who skates by the help effort, gets in the paint and drops off for a layup.

All of that comes as the result of one simple ball screen and Manek’s 3-point gravity.

The legendary Hubie Brown likes to say that offenses set screens for one reason: to make defenders think. That’s exactly what you’re seeing here.

Weak-Side Players: Be ready to make a play

These defensive stunts, closeouts and rotations are why second-side offensive players must be ready to make a play: shoot the ball, attack a closeout or make the extra pass for an open shot. Manek will put defenses into rotation, but North Carolina’s guards and wings must be ready to think quickly and make plays.

The presence of Walton (42 3P%) will also be a major help.

Playing two plus-shooters on the floor together will make things so much easier for North Carolina’s offense. Shooters like Walton and Manek can solve so many baseline offensive issues.

Place Walton on the weak side of the action — one pass away from Manek — and it should make for simple tic-tac-toe passing and wide-open spot-up 3s out of the pick-and-pop.

Walton still has room to grow as a shooter; the release must get faster. He had a fair number of 3-point attempts blocked last season. However, if he continues to improve as a catch-and-shoot bomber, look out. This guy has the chance to be the best shooter in the country at some point of his career.

Weak-side shooters aren’t the only ones that can benefit from the pick-and-pop gravity, though. Second-side gaps will open up, too, and off-ball cutters can exploit those rotations.

One of the things Virginia did so well around Jay Huff pick-and-pops this season was to play off his gravity. Huff would screen, pop and catch; as soon as he faced the basket, a cutter would zip through on a 45/diagonal cut.

Virginia would then follow that initial cut with a trail cutter. In this scenario, it certainly doesn’t hurt to have a monster off-ball finisher like Trey Murphy III.

During his time at UNC, Leaky Black has shown flashes as a cutter. Anthony Harris (57.1 2P% career) is a heady basketball player. Both guys should be opportunistic next season, hunting high-percentage looks as off-ball movers.

That goes for every wing on North Carolina’s roster, including Puff Johnson and Love when on the floor with RJ Davis.

On The Move

North Carolina took advantage of Maye’s shooting activity in a variety of ways. This included several movement components: pick-and-pops (obviously), pindowns and flares. Here’s a designed Iverson Flare (L) look from the 2018-19 season for Maye.

Kenny Williams cuts off a set of Iverson screen from Brooks and Maye; Cam Johnson trails under the formation and stacks behind Brooks. As soon as Maye screens for Williams, he runs the opposite way off staggered flares from Brooks and Johnson.

Johnson, who was the best shooter in college hoops that season, doubles as a powerful screener. Walton, UNC’s next great shooter, can unlock similar things.

Manek has shown the ability to shoot on the move and off screens, too. That’s a weapon for UNC. It can be really tough for big men, especially in college, to defend 23+ feet away from the basket, while running around screens and handoffs.

Drawing from Virginia, again: Tony Bennett’s club was at its best this season during a stretch in the middle of the year, when the Cavs went primarily to their inside motion/middle third offense.

This offense features a lot of off-ball screening concepts between three players in the center third of the floor. With the 7-foot Huff and 6-foot-8 Sam Hauser involved in most of these actions, it caused many problems for opposing defenses.

The upshot: it’s hard to defend tall movement shooters. UNC doesn’t need to run motion to get these looks, either. Shots like this can be generated out of a simple Horns set — like this Horns Throwback action from Oklahoma.

Combine the pindown and Manek’s pop gravity: there are a variety of ways to involve Manek and Walton together, away from the basketball.

Here’s a look at North Carolina’s Secondary B3 action — courtesy of Adrian Atkinson. With Maye as the trailer in secondary vs. Duke, UNC loads Johnson to the strong corner, which opens the weak side for a Maye pindown-and-pop with Williams.

Action like this is how UNC can blend both old and now — in terms of style and roster. Manek flowing into a pindown for Walton, and popping, is an easy way to space and create good looks.

Space Out

Over the course of his final two seasons with Oklahoma, Manek scored 1.11 points per spot-up possession, according to Synergy. During the 2020-21 season, Manek finished in the 91st percentile in terms of spot-up efficiency: 1.19 points per possession (61.6 eFG%).

Stash Manek in the corner or on the wing and he should help open up real estate elsewhere on the floor. Love and Bacot stand to benefit the most from the added space.

Going further: I’d like to see UNC juice its pick-and-roll offense by clearing out a corner and running empty-side pick-and-roll with Love (or Davis) and Bacot.

North Carolina can get to these looks out of continuity ball screen. However, there are plenty of other ways to unlock these angles, including UNC’s empty-side pick-and-roll with weak-side staggered screens as occupying action.

With the corner empty, there’s no natural help defender; this can make the reads very easy for Love. Have Bacot screen and roll hard; if two defenders come to the ball, Love can hit Bacot with a pocket pass and it’s an easy finish.

It’ll be hard enough for defenders to help off of Manek and Walton, even if they’re stationary simply spaced to the weak side. However, involve those two in some dummy action and things become that much more complicated for the defense.

On the weak side of the floor: have one of the wings and Manek set staggered down screens for Walton. Those pindowns tie up any potential weak-side defender that could help on Bacot.

Of course, if the pass isn’t there to Bacot, Walton may be open off the staggers. Manek could also be free after he screens and pops. In theory, Love is a threat to drive the ball. The same can be said for Davis, who could use this to get to his pull-up game.

Friends In Lo Places

Shape was an ideal fit for UNC basketball, in a variety of ways: a monster on the offensive glass (he led the nation with an 18.3 percent offensive rebound rate) who loved to facilitate in North Carolina’s hi-lo action. He was incredibly physical and played with an edge.

Here’s Sharpe making a nice read and touch pass to Brooks out of North Carolina’s continuity ball screen (CBS) offense.

The pieces around Sharpe, however, mixed with his own offensive limitations, ensured that his freshman season would be capped in terms of overall impact.

Unfortunately, with a shaky jump shot (a few floor-spacers), teams could adjust to these types of hi-lo looks. Florida State is a little bit of a different beast; Leonard Hamilton’s program wants to apply as much pressure as possible, at all times.

However, others teams were more willing to play off the post player who made the catch between the free-throw line and the arc. North Carolina bigs would turn and face, but with the paint clogged, the obvious hi-lo read was wiped away.

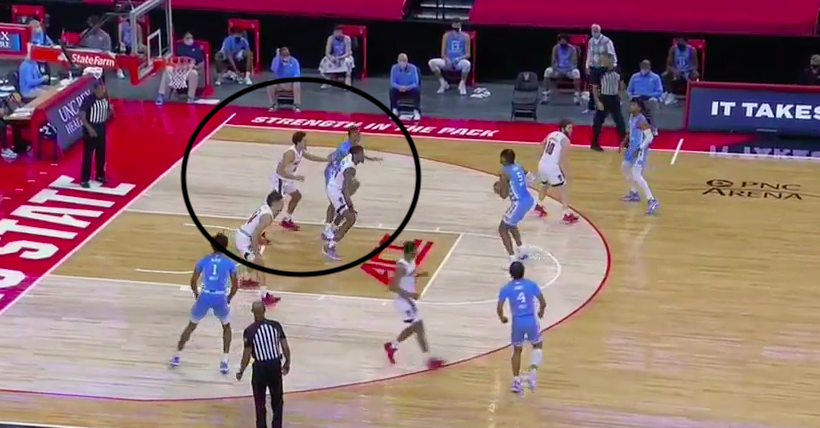

On this possession: Brooks has a size advantage over NC State’s Jericole Hellems, but with Manny Bates playing so far off Bacot, there’s no available passing angle or window.

It didn’t matter which pair of post players were in the game together last season; spacing remained an issue. Seemingly easy, would-be actions stalled amidst the congestion or resulted in turnovers.

Look how Ody Oguama and Isaiah Mucius of Wake Forest defend both Sharpe and Kessler on this CBS set.

Even if the passing lane opened up, the lo-man could still have issues in terms of initial catch/post position, and a lack of room to operate.

Here’s a look at UNC’s Horns Twist Hi-Lo — with roll-replace action (Sharpe lifting up as Kessler rolls). Kessler doesn’t have deep post position; he’s in an inefficient no-man’s land in the middle of the lane on the catch. Plus, regardless of which way he turns after the catch, a double team is waiting.

Once again, Wake Forest sinks Ismael Massoud deep in the paint, which denies Bacot the hi-lo entry. Davis, however, attempts to bail this possession out with a tough, spinning pull-up 2-point attempt.

Help Hi and Lo

Manek should absolutely be able to help North Carolina’s hi-lo action. While he doesn’t have the passing or processing skills of Sharpe, his jumper will force teams to play him tight. This will open up room at the rim for Bacot.

After struggling to finish around the basket as a freshman, Bacot improved dramatically during his sophomore season.

During his rookie year, Bacot shot 46.9 percent on his 2-point attempts. According to Bart Torvik’s shot data, Bacot shot 60 percent on close 2-point attempts. Those numbers jumped to 63.1 percent and 68.1 percent, respectively, in the 2020-21 season.

Day'Ron connects with Bacot with the hi-lo touch pass pic.twitter.com/7DtoD4sw9Y

— Trevor William Marks (@twmarks_) March 6, 2021

On top of that, Bacot’s free throw attempt rate grew (58.3 percent) as he drew 5.5 fouls per 40 minutes, up from 5.0 his freshman year.

Manek isn’t some super advanced playmaker; his career assist rate is below six percent. Even if assists are an imperfect measure of a player’s passing ability, that’s a pretty low number.

But, guess what? He doesn’t have to do anything too difficult here. Let Bacot carve out space, seal his man and get him the rock. Points and free throws will follow.

This will work across different modes of offense: in the half court and on the break. With Manek’s catch-and-shoot ability, he should function nicely as the trail man in North Carolina’s secondary break. Manek can look for his 3 or target Bacot on the rim run/seal.

Caleb Love: Deception at the Mesh Point

The success of North Carolina next season may largely depend on the development of Love. The second-year guard has talent, although he’s limited in ways that proved detrimental to functional half-court offense in the 2020-21 season.

Love’s lack of burst and inability to separate from defenders caused all kinds of issues. He forced tough, contested shots. Unsurprisingly, he missed the vast majority of those looks. It’s concerning how difficult it was for Love to reliably touch the paint with his handle.

At times, his decision-making was rough, too. Loved forced plenty of questionable passes.

If Love is unable to find another step, then he’ll need to up his craft as a creator and finisher. His layup and floater packages need improvement. (Per Synergy: Love shot just 36.2 percent around the rim in the half court.)

It would go a long way if Love could hit his pull-up jumper at a decent rate. If that switch flips, everything else becomes easier. During his freshman season, Love scored 0.66 points per pick-and-roll possession (32.8 eFG%, 29.9 FG%), according to Synergy.

Caleb Love finishes his freshman season with 305 points on 329 FGA — 32 FG%, 35 2P%, 27 3P%, 37 eFG%, 24% FTA rate

Struggled with burst, ability to separate from defenders. Cracking the paint off a live dribble never really came with ease. Pull-up shooting should improve, though

— Brian Geisinger (@bgeis_bird) March 20, 2021

Another thing to monitor with Love next season will be his ability to deceive and probe with the basketball, especially in ball-screen actions.

How manipulative can Love be at the screen? Can he force the big man defender to hesitate before running back to closeout on Manek in pick-and-pop action? When slivers of space open up, can Love get into those gaps and pressure the rim?

The answers to those questions matter for North Carolina’s offense and for Love’s stock as an NBA prospect, which took a hit this season.

Manek possesses very real gravity; opponents must be mindful of his location. This should be helpful for Love. It’s obvious that UNC’s personnel — and lack of spacing — further exaggerated Love’s on-ball deficiencies. Manek will help: both as a spacer and pick-and-roll partner.

There are a couple ACC teams that run switch-heavy defenses; FSU switches positions 1-5, while NC State switches 1-4 and drops the 5. Depending on personnel, Duke will switch 1-5, too. However, if Manek gets hot hitting 3s from the pick-and-pop, it’ll be interesting to see if that forces other less switchy defenses to switch on the action.

If that happens, Love must be ready; this will be his opportunity to showcase his development. That situation should be a green light to attack and get downhill. Again, if he can’t blow by bigger defenders, Love must have a counter.

Post Game: Brady Manek

Manek does most of his damage from deep; over 53 percent of his career field attempts at Oklahoma came from beyond the arc. But he can threaten defenses from multiple levels of the court, including the post.

Throughout his time in Norman, Manek was never a high-volume post-up option; he was better served as a spot-up or pick-and-pop weapon. But he still adds some offense down on the block and in the midrange.

If Manek catches a smaller defender in the post on a switch, he can go to work — even if a late double team arrives.

According to Synergy, Manek scored 0.78 points per post-up possession (37.7 FG%) across four seasons with the Sooners.

With Manek and Bacot set to play together a lot next season, UNC has a nice inside-out combination up front. (Although I do worry some about their collective foot speed on defense.) The lion share of those inside touches should belong to Bacot; however, the Heels can invert that on some possessions.

If Manek is partnered up with Justin McKoy, then he can venture down to the block some.

Who knows, maybe Davis decides to play more small-ball, especially if one of Manek or Bacot get into foul trouble. Black could slot in at the 4, an under-utilized option during his time at UNC. Dontrez Styles should get looks here as well.

Manek isn’t suited to anchor a defense all that well, but if he’s the de facto 5: it would juice the offense and allow Manek to move more freely all around the half-court, with space.

Never Delay

Davis is on the record saying that he plans to renovate North Carolina’s offense, while maintaining the core tenets of UNC basketball. Manek fits well into this hybrid approach.

However, I’ll be curious to see if Davis is willing to implement more 5-out sets, which have become all of the rage in college hoops. North Carolina could run what’s called Delay — a 5-out set that starts with the ball at the top of the key, usually in hands of the center. (This is a very common set in the NBA, too.)

Teams can run designed actions out of this set or flow into a read-and-react style of offense — launching handoff actions and pick-and-roll.

There’s a version of this that fits North Carolina’s personnel. Start the possessions with Bacot in the middle of the floor. Station Love in the left corner and place Manek on the weak side. From this setup, UNC could run what’s called Chicago action, which is a pindown screen into a handoff.

Jordan Sperber of HoopVision refers to these looks as “5-out zoom” action.

Xavier went to 5-out zoom action on today's game winner against Providence. They also scored off that same action just a few minutes earlier in the game pic.twitter.com/TFluR5pnNM

— Jordan Sperber (@hoopvision68) January 10, 2021

With Love in the corner, have him come off a pindown from Walton as Bacot dribbles to his left, in the direction of Love and Walton. As Love sprints off Walton’s screen, he enters into the handoff exchange with Bacot, who screens and rolls to the hoop; Walton lifts back up along the arc.

For example: the Charlotte Hornets love to use this action. When Gordon Hayward turns the corner and Bismack Biyombo rolls to the rim, Devin Booker tags the roll, which leaves Terry Rozier open for a 3. That could be Walton.

This is a hard action to defend or switch; everything happens quickly. From UNC’s sake, it would allow Love to gather steam (moving to his dominant right hand) and some advantage before he enters the handoff/screen-roll with Bacot, which would counteract some of his burst issues.

Manek’s presence on the weak side will force help defenders to maintain their integrity. Crash in off Manek and it’s an easy kick-out pass for a 3.

While Love turns the corner, have the weak-side wing do another 45/diagonal cut. If the defense is ball-watching or occupied with other parts of the offense, that cutter can steal a layup.

If the help defense reacts to that cutter, then Manek should be open for a spot-up 3. Watch here: as Hayward cuts through, Kyle Lowry helps and LaMelo Ball is open for a triple.

Finally, instead of having the weak-side wing cut through on the 45, that player can also set a pindown screen, which would free Manek up for another movement 3-pointer.

Read More on Brady Manek and ACC Basketball

Former OU teammate Alondes Williams set to have an impact at Wake Forest