In the children’s game of musical chairs, the rules are simple, and they have never changed.

There is always one more player than there are chairs. Whenever the music stops, the remaining players scurry to sit on an available chair. With each round, another chair is removed, and another player is eliminated. The cycle continues until only the winner survives. Everyone else loses.

In the big-money world of modern college athletics, the rules are complicated, and they keep changing, especially over the last 30 years.

This NCAA game gradually — and unexpectedly — has evolved into one in which there are five winning chairs. That may sound like a lot, compared to the children’s version, until you realize that 10 or more conferences, representing more than 100 colleges and universities, competed for those five chairs.

“The ACC is in a strong position right now, and well-positioned for the future,” Duke athletic director Kevin White said. “But looking back, there were times when the music was playing, and the anxiety was real, and the uncertainty was alarming, and we weren’t sure where we’d be when the music stopped.

“Fortunately, we found our chair. We’re not only still in the game, we’re in a very good place. We can never stop working to get better. But we can enjoy the music now, instead of worrying about whether it’s going to stop.”

Haves Versus Have-Nots

ACC commissioner John Swofford is a 68-year-old man in charge of a 64-year-old league that has found high-level success in many sports.

A football player at UNC from 1969-71, he grew up in North Carolina at a time when the ACC was far more famous for men’s basketball. Now he oversees a conference that benefits far more financially for its gridiron success.

“The world is a much different place now in that regard,” Swofford said. “For decades, as a conference, we made more headlines in basketball and more money in basketball, and there was nothing inherently wrong with that. Obviously, basketball remains a huge part of our success and identity today.

“But for various reasons, that picture has changed significantly. We’ve been through realignment and expansion multiple times, with football a major factor in that. We have an ACC football championship game now. We have a College Football Playoff. I think it’s fair to say that, without significant upgrades in football over the years, the ACC would not be where it is today.”

That’s an understatement.

It may be an overstatement to suggest that the ACC may not EXIST today but for its football improvements. However, if it did exist, without those upgrades, it might look more like the American Athletic Conference.

That’s a scary thought, because major college athletics is now divided between the haves and the have-nots along very clear, football-related lines: the Power Five leagues (ACC, Big Ten, Big 12, Pac-12, SEC) and the Group of Five leagues (AAC, Conference USA, MAC, Mountain West, Sun Belt).

The differences, financially and otherwise, were significant in previous decades. Those same disparities are downright gargantuan today.

Power Five leagues now offer shared-revenue distributions ranging from $25-$40 million per year per school. The others are in the $1-3 million range.

Power Five leagues averaged more than $65 million each per season over the first three years of the new College Football Playoff revenue distribution format. Group of Five leagues averaged less than $18 million each per season.

More David Glenn: Interviews from Operation Basketball 2017

Even beyond the money, the labels matter. During votes on football-related NCAA legislation, Power Five leagues get two votes each, while the Group of Five leagues get one each.

In the end, of course, the contrasts continue in virtually every conceivable direction. The Power Five have the most money, so they build the best facilities and attract the best coaches. Those things tend to attract the top high school prospects, which further perpetuates the cycle.

In one recent study, the SEC (315) had more players on 2016 opening-day NFL rosters than the entire Group of Five combined (302). Together, the SEC, Big Ten (245), ACC (226), Pac-12 (211) and Big 12 (134) contributed roughly two-thirds of the entire NFL population.

America Embraces Football

When Swofford became ACC commissioner in 1997, he succeeded Gene Corrigan, another man who had experienced college sports from many angles.

Corrigan played lacrosse at Duke from 1948-51, before the creation (in 1953) of the ACC. He became an ACC coach in the late 1950s, leading both the lacrosse and soccer programs at Virginia, and later served the Cavaliers as their athletic director (1971-81). He was the ACC commissioner from 1987-97.

When Corrigan left the ACC in 1981, Virginia was a Final Four team in basketball but a decades-long laughingstock in football, and that contrast symbolized the lingering perception of the conference as a whole. In his time as ACC commissioner, too, basketball garnered the majority of the superlatives.

Financially speaking, as well, basketball ruled the ACC universe. Every single year, through its first five decades, when the ACC calculated and divided its shared revenue (money from TV contracts, the NCAA Tournament, the ACC Tournament, bowl games, etc.), basketball was paying the majority of the bills.

During his six years away from the conference, Corrigan was the AD at Notre Dame (1981-87), long before the Irish’s affiliation with the ACC. It proved to be a football-first experience that left a lasting impression.

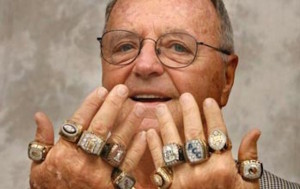

Corrigan took over an athletic department clearly led by a proud, popular, legendary, 10-time national champion gridiron program. He inherited forgettable football coach Gerry Faust, replaced him in 1986 with the unforgettable Lou Holtz, and watched from afar as Holtz led the Irish to the 1988 national title.

He didn’t completely realize it at the time, but with the benefit of hindsight Corrigan now knows he was a witness to the blossoming of American football.

“As athletic directors and commissioners, you focus on things within your control, and you try not to worry too much about things beyond your control,” Corrigan said. “What happened with football, back in the 1980s, is a great example of how our jobs in college sports were changing, without us totally seeing or comprehending it at the time.

“America was falling in love with football, and not just at schools like Notre Dame, where the fans had embraced football forever. This was about football as a TV product, and its appeal to the masses, and as an economic engine that would surpass even basketball in ways we hadn’t imagined.”

Indeed, public opinion polls at the time reflected this theme.

A 1985 Harris Poll of American sports fans indicated that the NFL (24 percent) and Major League Baseball (23 percent) were neck-and-neck as America’s favorite sport, after many decades with baseball clearly on top. College football was growing in popularity, too.

By 2011, in the same poll, almost half of American sports fans described football — either pro (36 percent) or college (13 percent) — as their favorite sport. The next-most popular answers were baseball (13 percent), basketball (10 percent), auto racing (8 percent) and ice hockey (5 percent).

The nation clearly had changed. As consumers, American sports fans wanted more and more football. The NFL and the NCAA, including the ACC, were happy to deliver. Gradually, television became the perfect vehicle for that.

TV Explosion=Huge Money

The next chapter of this story may sound like science fiction to younger generations, but all of these things actually happened and are 100 percent real.

Upon the ACC’s creation in 1953, less than half of American households owned a television. Even in the 1970s, by which time more than 95 percent of American households owned at least one TV, many were black-and-white (no color) sets, and few had access to more than seven or eight channels. Seriously.

While the first televised college football game came way back in 1939, and in a fun piece of pre-ACC trivia Duke visited Pittsburgh in 1951 for the first live national TV broadcast of a college football game, all the way through the 1970s there were only sporadic national and regional college football broadcasts.

The Big Three networks ABC, CBS and NBC collectively offered a few regular-season broadcasts (often split by region) every Saturday, then some variety of bowl games (there were only 8-11 per year) in the postseason.

For most of this stretch, by the way, it would have been difficult for the ACC to be less relevant in football. Through the entire 1960s, it failed to produce a single top-10 team. In the most extreme example of mediocrity and irrelevance, in 1964, none of the league’s eight squads finished with even a winning record.

It wasn’t until 1981, almost 30 years into its existence, that the ACC finally started to look as if it might belong in major college football.

For the first time, the conference had a game matching two top-10 teams, a frequent occurrence in ACC basketball. ABC broadcast the game live nationally, with Clemson edging UNC 10-8. When the Tigers went on to a 12-0 record, the national championship and a #1 final ranking, and the Tar Heels finished 10-2 and #9 nationally, it marked the first time the ACC had two top-10 teams in the final national polls. Again, that had become commonplace in hoops.

While the ACC didn’t experience similar football success again until the 1990s, a perfect storm of sorts was brewing, one that would catapult the entire college gridiron world into a new dimension.

Just as America’s love affair with football was blossoming, so was the number of television channels on which to enjoy it. Around the same time, in 1984, the United States Supreme Court — which rarely tackles college sports topics — handed down a decision that changed the sports TV landscape forever.

During the 1980s, cable television grew from a novelty act, with 16 million American household subscribers in the 1970s, into a true phenomenon, with 53 million. Cable networks, which numbered 28 in 1980, increased to 79 by 1989. Along the way, consumers went from watching 10 channels to wanting 100-plus.

ESPN, America’s first 24-hour sports network, launched in 1979. By 1982, it had carried its first live college football game, a bowl. TBS, another cable network, carried a more extensive slate of regular-season games that year.

Nevertheless, college football lagged far behind the NFL and other professional sports, and even college basketball, in terms of TV exposure. That was about to change in an authoritative, definitive, ever-lasting manner.

On June 27, 1984, the Supreme Court ruled in NCAA v. Board of Regents of the University of Oklahoma that the NCAA’s existing television policy — which had all of its members negotiating TV contracts jointly, through an organization known as the College Football Association — violated the Sherman Antitrust Act. As a result, for the first time, individual schools and conferences were permitted to strike TV deals on their own.

“That opened the door for so much of what you see today,” said seventh-year NC State athletic director Debbie Yow, the Maryland AD from 1994-2010. “For decades, ticket sales, booster donations and other things were driving the economics of major college athletics. Those two categories remain very important today, and always will be important, but it’s so different now.

“Nobody would have believed this in the 1980s, but right now more than half of our shared revenue in the ACC comes from our TV partners. We’ve doubled that number, doubled it again, then doubled it again. Over the last three decades, it’s been almost exponential growth. Now ACC Extra is here, and the ACC Network is on the way. You really can’t overstate the importance of that.”

Initially, the free-market approach to college football on television encountered turbulence. The quick saturation of available games in 1984 actually resulted in major declines in both advertising rates and individual game ratings.

However, the dramatic increase in exposure also encouraged more fans to fall in love with college football, and that’s exactly what happened. Viewership quickly rebounded, and the market quickly realized there was a monster to feed.

ESPN continued its dramatic expansion of college football coverage, which had included 48 game broadcasts in 1984. In 1993 came the debut of ESPN2, which launched a college football package in 1994. By 2005, there was so much valuable inventory that ESPNU (all college sports, all the time) was born, with heavy coverage of both marquee sports (basketball and football) from the start.

Here’s one more vivid illustration of the growing power of television, and TV dollars, in modern college football.

In 1983, the last season before the landmark Supreme Court decision, college football brought in about $70 million, collectively, for its broadcast rights. Adjusted for inflation, that’s about $169 million in 2016 dollars — for all conferences, all teams, all college gridiron games played in 1983, combined.

In 2016, ESPN paid more than that amount for ONE GAME. It was the national championship game, between Clemson and Alabama, but it was ONE GAME. As part of a 12-year deal that started with the 2014 season, ESPN pays an annual average of about $470 million for the three-game College Football Playoff, with the most valuable event obviously being the title game itself.

Expansion And Realignment

The ACC’s first 25 years offered zero evidence that the conference would be, or should be, included in this gridiron/TV/money revolution. Fortunately for the league, many of the big changes and decisions didn’t come until much later.

From the departure of South Carolina for independent status after the 1970 football season, through long-time independent Georgia Tech’s initial gridiron campaign as a league member in 1983, the ACC was a seven-member football conference, and it rarely offered more than a single outstanding team.

Clemson and UNC occasionally cracked the national top 10. Maryland and NC State sometimes were in the Top 25. Duke, Virginia and Wake Forest all ranked among the worst gridiron programs in the higher-profile conferences.

Were that still the snapshot of ACC football when the world changed, there would be no lucrative, long-term television partnership with ABC/ESPN, no preferential treatment for the league in the CFP, no big-money contract with the Orange Bowl, no ACC football title game, no ACC Network on the way.

ACC basketball was plenty good then, and it’s plenty good now, but that’s not enough in today’s world. That’s because, just within the last decade, multi-sport conference TV partners started describing the value in their multi-billion-dollar contracts as 80-plus percent football, less than 20 percent men’s basketball, and less than one percent all other sports combined.

Clearly, something had to change with ACC football. Heck, a lot of things had to change. In some cases, the upgrades came from within.

In 1982, Virginia found its greatest coach ever in George Welsh. UNC later hired Mack Brown, who led the Tar Heels to back-to-back top-10 seasons in 1996 and 1997. Wake Forest found its modern-day savior in Jim Grobe, who led the Demon Deacons to the ACC title in 2006. Even lowly Duke, after a half-century of mostly miserable results, eventually discovered David Cutcliffe.

Looking back at the first three or four decades of ACC history, it’s easier to see why few, if any — even among intelligent, informed, sometimes innovative commissioners and ADs — envisioned the need for conference expansion as an additional, even vital, part of the league’s gridiron solution.

In 1980, for example, there was not a single major college football conference with more than 10 members. Some had only six teams. The ACC was the smallest of the high-profile leagues, with seven members.

Meanwhile, there were 30 independent football programs in 1980, including five that finished that season ranked in the Top 25: Pitt, Florida State, Penn State, Notre Dame and Miami. Boston College, Georgia Tech, Louisville, Syracuse and Virginia Tech also were gridiron independents at the time.

Then came an unexpected lightning bolt, in 1989. After more than a century (1887-1989) of football independence, Penn State shocked the college sports world by agreeing to join the Big Ten. The Nittany Lions played their first football season as a conference member in 1993.

If the ACC had been contemplating expansion at the time, Penn State would have been viewed as a perfect fit. The respected university reflected the ACC’s proud commitment to the academic/athletic balance. The football program, led by legendary coach Joe Paterno, was a perennial powerhouse.

Even geographically, Penn State clearly was a better fit for the ACC than for the Big Ten. Based in State College, Pa., PSU is about a 325-mile drive east of the closest Big Ten member at the time, Ohio State. The nearest ACC member at the time was Maryland, located less than a 200-mile drive from State College.

“To be honest, we (the ACC) were asleep at the wheel,” Corrigan said. “With the benefit of hindsight, I know that may sound outrageous, but it’s the truth. We were absolutely stunned by the Penn State announcement.

“If there’s a silver lining to that story, it’s that we were awakened to the idea of expansion. Even then, not everyone in the ACC jumped immediately into expansion mode. But some of us wouldn’t stop talking about it. Although some schools resisted to the end, just enough came around to see it our way.”

Since Georgia Tech had started playing an ACC football slate in 1983, the ACC was an eight-team league with members in five contiguous states: Maryland, Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina and Georgia. The next state to the north is Pennsylvania, but the Big Ten already had grabbed Penn State.

The next state to the south, of course, is Florida. The Florida Gators were long-time, happy members of the powerful SEC. The independent Miami Hurricanes had just won their third gridiron national championship (1983, 1987, 1989) in seven seasons, but their renegade image (pay-for-play superfan Luther Campbell, 1988 “Catholics-Vs-Convicts” matchup with Notre Dame, etc.) alienated some decision-makers in the tight-knit, gentlemanly ACC.

Florida State, still a football independent in 1990, had inquired about membership in the SEC numerous times during the Seminoles’ rise to prominence under legendary coach Bobby Bowden in the late 1970s and 1980s. The SEC didn’t show much interest in return, at least not until 1990.

The ACC finally came calling in that same year. By then, FSU was three years into one of the most amazing stretches of success in college football history: 14 consecutive top-five seasons from 1987-2000.

“Those (1987-89) Florida State teams had more national television exposure in those years than all of our ACC teams had together,” Corrigan said. “The 1980s may have been the greatest stretch of basketball in ACC history, even to this day, and that provided a comfort zone for some. But we all knew we had to keep upgrading football, and adding FSU certainly provided that.”

At the time, an ACC expansion proposal required approval from six of the eight ACC schools to pass. The final tally was 6-2 in favor, with Duke and Maryland dissenting. Once the expansion concept passed, there was another vote on the recipient of the invitation. The Seminoles received all eight votes.

At Florida State, the university’s decision-makers clearly preferred the ACC over the SEC, largely for academic reasons. Bowden told his superiors he’d be OK with either league, and would follow their lead, but whenever asked he added that the ACC would be the better fit for one very specific football reason.

“The best road to a national championship was through the ACC, and there was no doubt about it,” Bowden said. “Could we beat the SEC’s best teams? Yes, and we often did. Could we finish first in the SEC? Yes, sometimes. But that league was so tough, top to bottom, that they beat each other up. You might finish first one year, but you might finish third, fourth in other years.

“Our number one goal every year was to win the national championship. We joined the ACC and played for the title five times in the 1990s, winning twice. The Hall of Fame calls when you have two national championships. I don’t think they call if you have too many third-place finishes.”

Because of the FSU-ACC marriage (1990 decision, 1992 debut), both of Bowden’s national titles (1993, 1999), 10 top-five finishes and six major bowl victories (three Orange, three Sugar) came with the Seminoles carrying the ACC football flag. Immediately, that 1992-2000 run qualified as the greatest gridiron stretch in the history of an almost 50-year-old league, and it wasn’t close.

Gradually, as Bowden’s description of ACC football indeed proved beneficial for the Seminoles, it proved embarrassing for the rest of the league.

In 1993, for example, on its way to the national championship, FSU played close, difficult non-conference games against Notre Dame (a loss), Florida (a win) and Nebraska (an 18-16 victory in the Orange Bowl title game). Meanwhile, in their five ACC home games, the Seminoles beat Clemson, Georgia Tech, NC State, Virginia and Wake Forest by an average score of 53-3!

Although Clemson and UNC did finish in the Top 25 that year, the ACC quickly became known as “FSU and the Eight Dwarfs” on the gridiron. In that initial stretch under Bowden, from 1992-2000, the Seminoles actually posted the unthinkable record of 70-2 in conference play, with nine straight ACC titles.

In the latter half of the 1990s, Georgia Tech and UNC also produced top-10 football teams, but at the turn of the century the ACC still lagged behind the other power conferences. From 2001-03, for example, the league didn’t have a single AP top-10 team, while over those same three seasons the Big Ten (six), Big 12 (eight), Pac-12 (six) and SEC (six) populated that elite level quite well.

Meanwhile, the SEC was more than a decade into its divisional format and lucrative SEC championship game, which launched in 1992. By 2003, the Big 12 and the MAC also had conference title games, which under NCAA rules required both the divisional format and a 12-team minimum. The ACC still had only nine.

You know the rest of this story.

With independent football programs mostly a thing of the past (there were only four by 2003, with Navy and Notre Dame the highlights), the normally genteel ACC turned conference cannibal. In 2003, the Big East had eight football members; by 2011, five were either in the ACC (BC, Miami, Virginia Tech) or on their way (Pitt, Syracuse). The ACC launched its football title game in 2005.

The themes were familiar: upgrade football, expand into new geography, renegotiate with TV partners, make a lot more money.

In the summer of 2003, the ACC voted to add two of the most successful football programs of the previous two decades. Neither offered even a hint of distinction in basketball, but it didn’t matter.

Miami brought a five-time national champion football program, plus the enormous South Florida media market. The Hurricanes were in the midst of four straight seasons of Big East championships and top-five national rankings. From 2000-02, the Canes had won 34 consecutive games, tying the sixth-longest streak in the history of college football.

Virginia Tech offered a legendary, in-his-prime coach in Frank Beamer, who had led the Hokies to 11 consecutive bowls. That included the 1999 national championship game, a 46-29 loss to Florida State. Tech would get its revenge as an ACC member, winning four conference championships in its first seven seasons, which was three more than the Seminoles won in that stretch.

Boston College, which arrived in 2005, provided elite-level academics, regular top-25 teams and another new, enormous media market. As with Miami, many wondered how many people actually cared about college sports in such a huge city with a pro-sports-first mindset, but the TV folks weren’t concerned.

Similarly, in 2011, after the ACC had voted to add Pitt and Syracuse (they began play in 2013), there were questions about adding two programs that had far more recent success in basketball than on the gridiron. Again, it didn’t matter.

At the time, then-Boston College AD Gene DeFilippo caught a lot of flak, and later apologized, for stating publicly that long-time ACC partner ESPN had played a major role in the league’s expansion decisions.

“You don’t get extra money for basketball. It’s 85 percent football money,” DeFilippo said. “TV — ESPN — is the one who told us what to do. This was football. It had nothing to do with basketball.”

Interestingly, nobody challenged DeFilippo’s 85 percent estimate. Many in the ACC and at ESPN were uncomfortable with the depiction of a media company playing puppet-master and further devastating the old Big East to the benefit of its long-time conference partner. But the bottom line was clear.

When the ACC grew to 12, it had both its championship football game and more positive gridiron news. Its NFL draft numbers jumped. It had more national TV matchups. In 2005, in another first for a then-53-year-old league, it placed five teams in the final Top 25: Virginia Tech, Miami, BC, Clemson and FSU.

Some Lingering Uncertainty

While this story itself is a reminder that looking too far into the future remains a tricky proposition, and more unforeseen variables could complicate this equation once again, the ACC in 2017 is in a stable, healthy place.

However, it hasn’t been the NCAA’s wealthiest conference for decades, after holding that title for many years, and it’s extremely unlikely to catch the SEC or Big Ten in that category any time soon.

Consider:

▲ With its 21st century expansions, the ACC quadrupled its money, although it also increased its number of mouths to feed. In 2004, its final year with nine members, the league generated about $110 million in shared revenue. By 2015, with 15 members, that number had soared past $403 million, and after an expected dip in 2016, the 2017 number will be even higher.

▼ Nevertheless, the ACC continues to lag well behind the SEC and Big Ten, and it sometimes trails the other Power Five leagues, too. In 2014-15, the SEC ($32.7 million) and Big Ten ($32.4M) were well ahead of the ACC ($26.2M), Pac-12 ($25.1M) and Big 12 ($23.4M) in shared revenue distributions per school. In 2015-16, the SEC surpassed $40 million per school, the Big Ten reached $35 million, and the Big 12 ($30M) and Pac-12 ($27M) leapfrogged past the ACC ($24M).

▲ Unlike in the Big 12, where merit-based revenue sharing and wealthy superpower Texas (Longhorn Network, etc.) eventually caused so much resentment that four schools departed for other Power Five leagues and the conference nearly disappeared completely, the ACC has cultivated much more camaraderie among its members. Thanks to near-equal revenue sharing and deep-rooted, positive relationships of 40-60 years, at least three ACC schools (Georgia Tech, UNC, UVa) turned away realignment inquiries from the Big Ten earlier this decade, despite realistic promises of making much more money there.

▼ Maryland, a founding member of the ACC in 1953, left those 61-year relationships in the dust in 2014, opting for the undeniably stronger financial numbers and projections offered by the Big Ten. (The Terps and the ACC ultimately settled their competing lawsuits by agreeing to a $31.4 million exit fee, rather than the full $52.3 million.) Around the same time, many Florida State fans argued in favor of a move to the similarly wealthy SEC, although key FSU administrators clearly preferred the option of building upon 20-plus years of success in the ACC, with a few tweaks to the league’s plan.

▲ The ACC Network, a 24-hour TV channel that will launch by August 2019, will provide massive exposure and — most importantly — a brand-new, major revenue stream for the league. By partnering with ESPN, as the SEC did in 2014 with the immediately lucrative SEC Network, the ACC expects to avoid the distribution problems that have plagued the Pac-12 Network since its debut in 2012. In its first year, the ACC Network will carry 450 events, including 40 football games and 150 (men’s and women’s) basketball games.

▼ Even if the ACC Network is very successful, as expected, the ACC’s lengthy delay in making it happen has created a canyon-sized financial gap between it and the Big Ten and SEC. Thanks in part to the success of the Big Ten Network (which launched in 2007 and reportedly became profitable in 2009) and the SEC Network, those leagues both project annual payouts exceeding $50 million per school by 2023. Even with immediate profitability, the ACC Network will leave the league in catch-up mode.

▲ Finally, the ACC in 2016 had arguably its greatest football season ever. Clemson won the national championship, giving the ACC two of the last four titles. (Florida State won in 2013.) FSU captured the Orange Bowl and earned another top-10 ranking. Virginia Tech, Miami and Louisville also finished in the Top 25. Never, in its previous 63 years of existence, had the ACC had two top-10 and five Top 25 teams in the same season.

The league had 11 bowl teams and tied the all-time record for any conference with nine bowl victories (9-3). Counting the regular season, the ACC even finished 10-4 against the SEC and 6-2 versus the Big Ten. One more thing: Louisville quarterback Lamar Jackson won the Heisman Trophy. Not bad.

All of that came in the immediate aftermath of the big news last summer, about the on-the-way ACC Network, the lucrative new TV deal with ESPN all the way through 2035-36, and — another biggie — the extension of the league’s grant-of-rights arrangement, all the way through 2035-36 as well. That makes it insanely expensive for any current ACC member to leave any time soon.

Largely because of these developments, whatever music might be playing over the next 19 years, whatever strange twists and turns may be coming its way, the ACC knows it will continue to have an important chair at the NCAA table.

David Glenn, the Founding Editor of the ACC Sports Journal and ACCSports.com, remains a consultant and contributor to both outlets. Now in his 30th year as a professional journalist, he serves on the Executive Committee of the Atlantic Coast Sports Media Association (ACSMA), which conducts the league’s All-ACC voting and works with the conference on media-related matters. He’s also a long-time member of the United States Basketball Writers Association (USBWA), the Football Writers Association of America (FWAA) and the National Sports Media Association (NSMA).

Glenn also hosts the David Glenn Show (@DavidGlennShow), one of the largest regionally syndicated sports radio programs in the nation, heard on 25-plus AM/FM signals in 250-plus cities and towns across North Carolina, plus parts of South Carolina and Virginia. In 2014, Glenn became the first person working primarily in the sports-talk-show genre ever honored as the North Carolina Sportscaster of the Year, an NSMA award first given in 1959.