This feature article was originally printed in our 2018 ACC Basketball Preview in September 2018.

Decades ago, the NCAA rules in place at the time made it truly impossible for a college basketball team to even attempt an ACC or national championship run with superstar freshmen leading the way.

A few years from now, because of expected changes to NBA draft rules, the same sort of path immediately will become so extraordinarily unlikely that it may be a mere stutter-step short of a true impossibility.

In between, the 2018-19 Duke basketball team, led by some combination of four NBA-bound, five-star freshmen, will try to make history.

The Blue Devils’ four best players are expected to be (in whatever order) point guard Tre Jones, wing forwards RJ Barrett and Cameron Reddish, and power forward Zion Williamson. They were considered four of the top 10 high school seniors in America last season, with Barrett (#1), Reddish (#2) and Williamson (#3) atop the consensus big board.

“The way things appear to be going, the window may be closing on one-and-done college players,” said new Pitt coach Jeff Capel III, Duke’s top assistant coach and recruiter under Mike Krzyzewski in recent years. “It’s very possible that we’ll never see anything like this Duke team again.”

When Freshmen Were Ineligible

Way back when Coach K was playing college basketball, as a point guard from 1966-69 for his mentor Bob Knight at Army, NCAA rules strictly prohibited freshmen from playing at the varsity level. After the mandatory one-year adjustment period at West Point, Krzyzewski averaged about six points per game over what was the standard, three-year varsity career.

“There were times I wasn’t sure Coach Knight liked me even when I was a senior, and I was a team captain that year,” Krzyzewski said, laughing. “In my case, it was probably best that I didn’t play (varsity) as a freshman. I might not have ever made it to my sophomore year if I did.

“But the world has changed a lot since then, obviously, and I wasn’t anything close to an elite high school player, like so many of our guys here at Duke. We didn’t change the (NCAA/NBA) rules, but we all have to play by them, and sometimes for us that has meant a number of one-year players.”

The logic behind the NCAA’s original restriction against freshman eligibility involved a complicated mix. In the late 1960s, many universities were reacting to both the influx of African-American athletes and the mandates of federal Title IX legislation (which led to the explosion of women’s varsity sports) for the first time, while also feeling the financial stress of fielding both varsity and junior varsity teams in many sports.

In 1968, the NCAA finally allowed freshmen to compete in other sports, but not football and basketball. Only in 1972, the same year that earlier saw NC State legend David Thompson average almost 36 points per game for the Wolfpack’s freshman basketball team, was the restriction lifted entirely.

As a result, whereas a list of the ACC’s greatest performers here in the 21st century would include a bunch of one-year players and other early NBA entries, that same list from the league’s first two decades would include lots of elite three-year players. Thompson and others likely would have been freshman sensations, too, but NCAA rules prevented that from happening.

When Freshmen Became Eligible

Sure enough, as early as 1975, an ACC freshman proved worthy of both first-team All-ACC honors and early entry into the professional ranks. Clemson guard Skip Wise averaged 18.5 points per game for the Tigers, then signed with the Baltimore Claws of the old ABA.

Thus, the ACC’s version of the one-and-done concept was born more than four decades ago, albeit as a true rarity, even nationally.

Although the ACC often provided the best college basketball had to offer through the 1970s, 1980s and 1990s, including signing a plethora of prep All-Americans and eventually turning many of them into high NBA draft picks, the now-eligible freshmen only rarely dominated. In fact, after Wise, it wasn’t until 1990 that another rookie (wizard-like Georgia Tech point guard Kenny Anderson) earned first-team All-ACC honors.

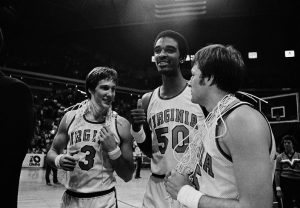

During the 1980s, which many consider the golden years of ACC hoops, early NBA entry became a slightly more popular phenomenon, but not the one-and-done variety, and not for everyone. James Worthy and Michael Jordan each played three years at UNC. Three-time national player of the year Ralph Sampson (who turned down $1 million from the Boston Celtics as a high school senior) played all four years at UVa, despite offers from professional teams after each of his first three seasons in Charlottesville.

“I think most of us looked at the world differently back then. I know I did,” Sampson said. “I was a very shy guy, even in college. My family didn’t need the money, and I needed time to grow as a person. I’ve made some bad decisions in my life and career, as we all do, but that wasn’t one of them.

“Looking back, I don’t do the what-if thing, with my injuries (which limited and shortened his professional career) or anything else. I enjoyed my time at UVa, and I enjoyed my time in the NBA.”

Even through most of the 1990s, in the eyes of the ACC’s superstars, the pull of the NBA draft wasn’t nearly as powerful as it is today. Duke’s Christian Laettner, Duke’s Grant Hill and Wake Forest’s Tim Duncan were elite collegians but stayed in school all four years. (Each became a top-three pick as a senior.) UNC’s Vince Carter and Antawn Jamison both played three seasons for the Tar Heels before leaving as top-five picks in 1998.

Early Entry Grows Exponentially

Nationally, however, early NBA entry was in the process of an explosion during the 1990s. What was once a trickle became a flood.

In 1991, for example, only 12 college and international players attempted the jump. Anderson, a Georgia Tech sophomore, was picked second overall. Billy Owens, a Syracuse junior, went third. In the end, six early applicants were selected in the two-round draft, and six were not.

For various reasons, the rest of the 1990s changed this dynamic forever. As Jordan soared, leading the Chicago Bulls to six championships, so did the NBA’s popularity, TV dollars and marketing appeal. At the same time, more top prep players adopted a year-round schedule that enabled them to hone their skills with and against other elite talents on the summer/AAU circuit, leading to far more college-ready freshmen than in past generations.

Meanwhile, in 1995 (Kevin Garnett), 1996 (Kobe Bryant) and 1997 (Tracy McGrady), three prominent high school seniors opted to bypass college altogether. All three entered the NBA as lottery picks, and all three became superstars, on and off the court.

While there had been rare cases (e.g., Moses Malone, Darryl Dawkins, Bill Willoughby) in the past of prep players jumping straight to the pros in the 1960s and 1970s, these mid-1990s examples — just as the internet was exploding — changed the attitudes of many American prep stars forever.

“There was always the guy who would say (as a high school player) he was ready for the NBA right now, and we’d all laugh and keep going,” Carter said. “Those (mid-1990s) guys changed the narrative. They proved it could be done, and nobody was laughing. The upside was they opened doors for guys like LeBron James (2003 NBA entry) later. The downside is that there’s probably 100 guys who think they can do it for every one who can do it.”

By the 2000s, the early entry number often exceeded 100 per year, sometimes with a heavy ACC flavor. When the league had nine players picked in the 2005 draft, only two were seniors.

UNC forward Marvin Williams, who didn’t even start for the Tar Heels and had no one-and-done thoughts upon his arrival in Chapel Hill, ended up making the leap unexpectedly as a freshman in 2005. Carolina had won the national championship that year, and he was told he’d make more than $18 million as the NBA’s second overall selection.

“It sounds like a lot more guys today get to college already having one eye on the NBA, and that’s OK for them,” said Williams, who took summer-school and online classes for 10 consecutive offseasons and received his UNC diploma in 2014. “I was in no rush to get to the NBA. I enjoyed my time in Chapel Hill so much I still go back every year, and North Carolina (where he still plays for the NBA’s Hornets) has become home to me.

“I know it’s hard for some fans to understand, because they love their school and they love college basketball, but put yourself in these players’ shoes. When you are given an opportunity that could provide financial security for a lifetime, you have to listen, and it’s very hard to say no.”

The same year (2005) Williams entered the NBA, a record nine prep seniors were chosen on draft night. The league loved welcoming LeBron in 2003 or even Dwight Howard in 2004 — both were selected first overall — but its teams didn’t like sending scouts to an endless number of high school gymnasiums, and they grew weary of wasting money on players who hadn’t been asked to prove themselves against a higher level of competition.

So starting in 2006, the NBA altered its draft rules, making high school prospects ineligible until one year after the graduation of their class. With that end of prep-to-pros, of course, came the acceleration of one-and-done. Almost all of the very best prospects are spending that extra year in college.

Fast forward to this past summer, when there were a record 236 names on the NBA’s early entry list, including 181 from the American college ranks. Twelve of those represented ACC schools, including five one-and-done freshmen, four of them from Duke: forwards Marvin Bagley III and Wendell Carter Jr, and guards Gary Trent Jr and Trevon Duval.

As the second overall pick this year, Bagley will make about $16 million (guaranteed) over his first two seasons with the Sacramento Kings. Then the Kings will have team options for about $9 million and $11 million entering years three and four, respectively. Bagley also signed a five-year footwear and apparel deal with Puma, reportedly worth $10-15 million.

Following Freshmen Isn’t Easy

Perhaps it’s not mere coincidence that, in the one-and-done era, one of Duke’s NCAA champions hardly relied on freshmen at all, while the Blue Devils’ most disappointing teams came with a freshman leading the way.

In 2010, when Duke captured the fourth of Coach K’s five NCAA titles, the five Devils who played the most minutes were seniors Jon Scheyer, Lance Thomas and Brian Zoubek, plus juniors Kyle Singler and Nolan Smith. The only freshman who played much, Mason Plumlee, averaged only four points and three rebounds per game.

“That was sort of our throw-back team. You could have built a team that way in the 1970s, 1980s or even the 1990s,” Krzyzewski said. “Most of those guys were learning and growing together for three or four years. At our level, it’s a lot more difficult to build a team that way now.”

Meanwhile, in Coach K’s 38-year career at Duke, he’s been eliminated in the NCAA Tournament’s Round of 64 only four times: in 1996, 2007, 2012 and 2014. His 1996 and 2007 teams simply weren’t very good; they’re his only squads since 1984 that failed to post a winning record in ACC play.

The 2012 and 2014 disappointments directly involved — you guessed it — freshmen. While highly regarded rookies and one-and-done phenoms Austin Rivers and Jabari Parker both lived up to the hype in some ways, their only Duke teams both fell far short of their collective goals.

Rivers and Parker clearly were the best players on those teams. They were the only Devils to earn first-team All-ACC honors, and each was named the conference rookie of the year. At the conclusion of their one and only year in Durham, each became a top-10 draft pick and an instant millionaire.

Neither Duke team, though, built the sort of chemistry or toughness that have become program trademarks. In the end, Rivers and Parker came and went without experiencing a regular-season title, an ACC Tournament championship or even a single NCAA Tournament victory. Their legacies also will include March Madness losses to Lehigh and Mercer, respectively.

Over the last 30-plus years, only four Coach K-led teams went 0-for-3 in those important categories. Two of those squads just weren’t good enough. The other two either never learned or liked to follow the freshman.

Elite Freshmen Still Worth Risk

If there is a king of the One-And-Done Empire in college basketball, it’s Kentucky coach John Calipari. He embraced the concept as quickly as anyone, then embedded it into his brand with the sheer volume of prep signees who used UK as a one-year stopover on their way to the NBA.

The Wildcats’ long list of one-and-done players is led by John Wall (2010), Anthony Davis (2012) and Karl Anthony-Towns (2015). All became first overall picks in the NBA draft, and all continue to enjoy lucrative, successful professional careers. Overall, UK has had more than 20 one-and-done players, far more than any other program.

In the 12 seasons since the NCAA changed its draft rules, and prevented high school players from jumping straight to the pros, Calipari’s Memphis and (starting in 2009-10) Kentucky teams have advanced to 10 Sweet 16s, eight Elite Eights, five Final Fours and three NCAA title games.

In 2012, when Calipari broke through for his first (and to this point only) national championship, he did so with three one-and-done freshmen in his starting lineup: Davis, forward Michael Kidd-Gilchrist and point guard Marquis Teague. All three then became first-round NBA picks.

Calipari actually says he doesn’t like the NBA’s current draft rules, which created the one-and-done phenomenon, even though they so frequently have benefitted his career and his teams.

“Both the NBA and the NCAA have made a habit of restricting these kids, just in different ways,” Calipari said. “If somebody wants to go straight to the league out of high school, let him go. If he wants to go to college and then leave, let him go then, too. Why would we force someone to stay?”

But he also is absolutely unapologetic for his role in making one-and-done work for both his UK program and his players in the meantime.

“Here’s what I say to the critics: What if that was your child? Would you be so upset about one-and-done then?” Calipari said. “We’re helping them with their dream of making the NBA. We’re positioning them to make a lot of money. At the same time, we’re offering them an education for as long as they want it, plus the structure of a successful basketball team.

“Then, on the back end, if they do leave early, we tell them they can return to school whenever they want, if they want, at our expense. If that’s your child, you wouldn’t want those options?”

Duke wasn’t quite as quick to embrace the one-and-done culture, but soon after the Blue Devils did the approach paid off with a national championship for them, as well.

Although Corey Maggette (1999) and Luol Deng (2004) technically qualified as Krzyzewski’s first one-and-done players, those weren’t according to any master plan. Maggette left after jeopardizing his eligibility by taking impermissible benefits, and Deng surprised everyone by evolving so quickly that he unexpectedly emerged as a top-10 draft pick.

It wasn’t until 2011 that Kyrie Irving became the next Duke player to take the same route, followed by Rivers and Parker shortly thereafter.

Finally, before the 2014-15 season, Coach K took a bigger plunge — even bigger than he thought at the time — into the one-and-done waters, and it ultimately paid off with his fifth national championship.

As with the 2012 Wildcats, the 2015 Blue Devils had three one-and-done freshmen in their starting lineup when they won it all, and at the same three positions. Both teams turned three prep All-Americans into national champions into first-round NBA picks into guaranteed multi-millionaires.

Center Jahlil Okafor had arrived in Durham with a one-year plan, and forward Justise Winslow knew it was a possibility. Point guard Tyus Jones played so well so quickly that he, too, was told after the season that he’d be a first-round pick. Okafor went third overall, Winslow 10th and Jones 24th.

Perfect Formula Truly Elusive

Whether looking back or forward, it’s vital to remember that 2012 Kentucky and 2015 Duke have even more in common than being history’s only examples of riding a trio of one-and-done rookies to the NCAA title.

In both cases, multiple upperclassmen — including an essential senior — provided an all-important supporting cast.

“Everybody remembers the freshmen, and I understand that, because those were amazing freshmen,” said Capel, Duke’s associate head coach in 2015. “But I’m not sure everybody remembers the rest of the story, and that would be a shame, because there were other essential pieces to the puzzle.”

The 2012 Wildcats also started two seasoned sophomores, guard Doron Lamb and forward Terrence Jones. Senior forward Darius Miller, a part-time starter and otherwise superb sixth man, averaged 10 points and three rebounds per game.

The 2015 Blue Devils also started senior guard Quinn Cook and junior forward Amile Jefferson, two players with extensive previous experience. Sophomore Matt Jones offered three-and-D support, mostly off the bench.

How many remember, just three years later, that Cook was actually the Devils’ second-best player that season? He averaged 36 minutes and 15 points per game, earning second-team All-ACC honors. Only Okafor, the first freshman ever to become the ACC player of the year, had a better campaign.

In theory, Duke’s 2017-18 team had a chance to follow in similar footsteps. Once Grayson Allen decided to stay for his senior year, he could blend his All-ACC talent and experience with the four prep All-Americans (Bagley, Carter, Trent, Duval) who proved to be one-and-done freshmen.

The problem was, there was almost nothing on the Duke roster between Allen as the lone scholarship senior and an enormous, seven-man freshman class. The starting five of Allen and the four star freshmen scored a whopping 75 points per game for a team that averaged 84.

It wasn’t supposed to be that way. But the Blue Devils experienced one of the very real but often unmentioned downsides of the one-and-done approach to winning; they had lost via early attrition not only the predictable (and sometimes unpredictable) early NBA entries, but also outgoing transfers who either didn’t see their lottery dream coming true in Durham or grew tired of waiting behind the superstars who did.

In the three years leading into last season, Duke had endured the transfers of wing forward Semi Ojeleye (SMU), point guard Derryck Thornton (Southern Cal) and power forward Chase Jeter (Arizona), plus the less predictable early NBA exits last summer of freshman point guard Frank Jackson and sophomore wing guard Luke Kennard.

With Kennard and some other early NBA entries, it’s easy to anticipate their decisions by the end of their best college seasons, but by then it’s often too late to find a high-end replacement on the recruiting trail. After a solid but unspectacular freshman year, when he was only a part-time starter, Kennard became a first-team All-ACC pick and the 2017 ACC Tournament MVP. Months later, he heard his name called late in the NBA lottery.

“Everybody can see the ideal approach, where you’re blending the most talented freshmen in America with quality three- and four-year guys who gradually earn their time in your program,” Capel said. “But at this point, I think everybody also sees that approach is easier said than done, and really there are only a few programs that even have a chance to try it.”

Another Rule Change Expected

While it may seem overdramatic to suggest that the 2018-19 Blue Devils will be one of the “last” teams with a chance to turn multiple one-and-done freshmen into a run at the ACC and/or NCAA championships, a quick check on America’s changing basketball landscape suggests otherwise.

At the end of August 2018, in what was considered by many a huge step toward eliminating the current one-and-done framework, the NBA, the National Basketball Players Association, the NCAA and USA Basketball announced a joint effort to create an organized system to identify, educate, cultivate and assist elite high school prospects with NBA potential.

Also this summer, the Rice Commission on College Basketball recommended the abolition of the NBA’s age limit. Meanwhile, NBA commissioner Adam Silver (a Duke graduate) re-stated his desire to do exactly that, preferably beginning with the 2021 or 2022 draft.

A current high school freshman who’s invited into the new NBA-USA Basketball program, which also will provide access to doctors, nutritionists, athletic trainers and even life-skills training, theoretically will be eligible to go straight to the NBA soon after his high school graduation in 2022.

Even if the NBA returns to rules that once again allow for the prep-to-pros avenue, as expected, there will be other details to iron out. For example, will basketball adopt baseball-like draft rules, under which a prospect who doesn’t sign straight out of high school isn’t eligible again until two years later? The baseball rules require a three-year interim in most cases, although a two-year wait (if any) may be more likely in basketball.

If any version of those changes comes to fruition soon, this year’s Duke roster — led by the four superstar freshmen, each with clear NBA potential — quickly will become a thing of the past. All four would have had the option of going straight to the NBA. Some of the Blue Devils’ current upperclassmen likely will play professional basketball, but perhaps none will make the NBA.

There’s certainly nobody like Cook to help Barrett, Jones, Reddish and Williamson this year. For that matter, there’s nobody like Allen, either.

Will such extreme levels of inexperience prove too much to overcome? Or will such extreme levels of young talent prove too tough to beat?

Either way, Coach K has a truly unique situation on his hands. The Blue Devils have an extremely unusual roster, facing an extremely unusual challenge. Since that challenge may be in the process of becoming extinct, it offers the GOAT — and this year’s sensational freshmen — a chance to grab an unprecedented, and perhaps insurmountable, piece of history.

David Glenn, the Founding Editor of the ACC Sports Journal and ACCSports.com, remains a consultant and contributor to both outlets. Now in his 31st year as a professional journalist, he serves on the Executive Committee of the Atlantic Coast Sports Media Association (ACSMA), which conducts All-ACC voting and works with the conference on media-related matters. He’s also a long-time member of the United States Basketball Writers Association (USBWA), the Football Writers Association of America (FWAA) and the National Sports Media Association (NSMA).

Glenn also hosts the David Glenn Show (@DavidGlennShow), one of the largest regionally syndicated sports radio programs in the nation, heard on 25-plus AM/FM signals in 250-plus cities and towns across North Carolina, plus parts of South Carolina and Virginia. In 2014, Glenn became the first person working primarily in the sports-talk-show genre ever honored as the North Carolina Sportscaster of the Year, an NSMA award first given in 1959.